Her nom de filmmaking comes from an infamous 19th-century murder, but Lizzie Borden is always ahead of her time. The leftist revolutionaries in her 1983 work of white-hot agitprop, Born In Flames, rebel against a neoliberal government, a schism familiar to anyone who has followed a recent Democratic primary. And her 1986 film Working Girls, chronicling a day in the life of an escort working a double at an upscale Manhattan brothel, was produced during the so-called “feminist sex wars” of the ’80s, where anti-porn and anti-sex work crusaders faced off against activists who argued that the right to express themselves sexually was key to women’s liberation—another debate still raging in academia (and on social media).

Working Girls is a slice-of-life drama that emphasizes the daily routines and little annoyances that make sex work a job like any other—the basket of sauce packets on top of a fridge in the communal kitchen, squabbles about scheduling and mid-afternoon drugstore runs—while frankly presenting the unique dangers and stigmas these women face. The film is told from the perspective of Molly (Louise Smith), a bohemian photographer who has yet to tell her girlfriend how she earns her money. Molly doesn’t mind being an escort so much; most of her clients are harmless regulars, and she actually enjoys talking to some of them. But when she’s asked to stay for a second shift by her needling, manipulative madam Lucy (Ellen McElduff), Molly begins to question if this is really what she wants to be doing with her time.

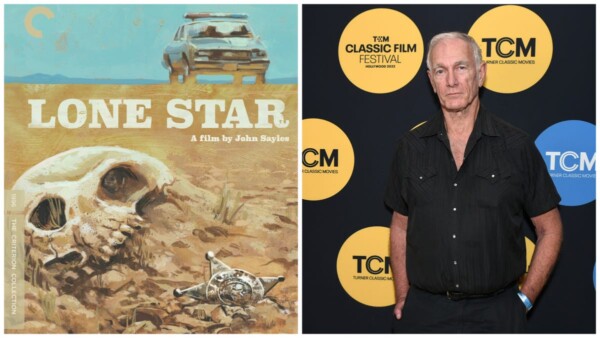

Quotable and brazen, relatable and revelatory, Working Girls premiered at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival. And despite positive reception from critics— “by the end of this movie, you wonder where [sex workers] find not only the patience, but also the strength” to do what they do, Roger Ebert wrote in his review—it all but disappeared for several decades. That was due to mishandling of the film by its distributor, Miramax, which tried to sell this pointedly anti-erotic film as titillating softcore. Now Working Girls been restored and is being re-released in theaters, as well as in a deluxe DVD/Blu-ray edition from The Criterion Collection.

We spoke with Borden about re-releasing and re-contextualizing the film, as well as the ways Working Girls comments, with typical prescience, on questions about work many are considering in the wake of COVID-19. The transcript of the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The A.V. Club: Would you describe this film, at its core, as a critique of capitalism?

Lizzie Borden: Absolutely. It’s funny—I have that line in [the film] where Molly says to Lucy, “Have you ever heard of surplus value?” I thought it was too intellectual to have in there [at first]. But then I thought, “You’re the capitalist. You’re the villain. You are stealing my time by making me work a double shift that I did not want to work.” Particularly with [sex work], the emotional labor on top of the physical labor adds up. And so that line is the cornerstone of the whole thing.

AVC: You see that emotional labor aspect when Molly’s with her clients.

LB: I’ve said this elsewhere, but I keep coming back to it: The best compliment I ever got about the film was from a guy who said, “I had a boss just like that.” I was really asking questions about jobs in general: What is work? How many people actually love the jobs they have? Which jobs are the most draining? It’s so American, thinking that work is good. But what does it actually take from you?

AVC: I was in college in the early 2000s, and they told us, “if you love your job, you’ll never work a day in your life.” But something that I think a lot of people are realizing now is that a job is a job. And I think this film speaks to that.

LB: So many things are wrongly valued in this culture, and valued against women, especially. That has not changed. Women are still paid less. It’s really about women’s labor in particular. I was always fascinated by the work of any service occupation. In waitressing, what do you do? The money, the ketchup bottles. [In the film] it’s putting out all the things you need—the Kleenex, the condoms, the towels—because that’s also part of what is expected by the madam. She’s not paying them for that. And then the madam swans in there with the things she bought. I wanted it to be clear that she was the villain and not the men, even though the men could be cruel at times. Had Molly not been forced to work a double shift, she would have been able to handle them. But because she was forced into exhaustion, she was vulnerable.

AVC: So it’s the condition she’s working under that’s exploitative, not the act of having sex with someone for money?

LB: Molly has to perform being a working girl, performing straight, all of that. But we all have to perform being a working person at times! You lounge around the house in your sweats—which a lot of people have been doing during COVID—and then you think, “Oh, my God, I have to wear those shoes.” The performance of the suit, or whatever, is being redefined post-COVID.

AVC: All these jobs—waitressing jobs in particular—that require women to wear high heels, I don’t know how they do it.

LB: The performance of work identity is very interesting, because everyone has their work style, which is not necessarily the same as the one at home. In terms of the women who work in that brothel, they all have their persona. They all put on identities. So there are similarities—except for the sex act. That’s another thing I wanted people to think about, but this was in the ’80s. Younger women have a very different sense of this.

Back then, there was a lot of transactional sex. There was a gimlet eye on casting couches. All that was going on, and everybody was like, “Oh, yeah, how did you get that job? You must have slept with the director.” But especially coming from a bohemian world—what’s the difference between actually getting money [for sex], or getting something else? Getting your rent paid, or getting somebody to do you a favor. What is the moral difference?

AVC: We’re back in a moment, at least online, where we’re returning to the feminist sex wars of the ’80s. How do you feel seeing these cycles repeat themselves?

LB: I think it repeats itself because there was such resistance for such a long time to even saying the word “feminism.” There was this total rejection of the word, then it was picked up again and reinvented. It’s different generations returning to feminism and reinventing words for themselves by rejecting the experiences of [previous generations], because it came in a different form back then.

In some ways it’s okay, because it’s bringing with it a whole set of new language. For example, the feminism of the ’80s was fairly binary. But one of the great things [about feminism now], even though I feel that so many women’s issues have moved backwards—choice is in a horrible place with these six week bans—but over time, there has been so much change in terms of gender, and being genderqueer, and the transgender [community]. Rachel Maddow is the No. 1 news person right now and she’s gay and she’s married to a woman. RuPaul’s Drag Race is popular culture!

The big battle in the ’80s was, “oh my God, if you’re a feminist, you’re a lesbian.” [Laughs.] I remember with Ms. magazine, there was a big fight because people thought the name “connoted lesbianism.” They put pieces by lesbians in the back, because they wanted to show that feminism “does not mean lesbians.” Then the issue with pro-porn and anti-porn feminists, that was number two. So everything was binary. You had to be for or against one or the other. Now the shades of difference are so narrow, and some of that comes from academia. Academia can be difficult, because there are so many self-defined words and battles within it. Some of the women, trans women, that I know who have come out of [academia] have battle scars from it. But it’s interesting that these words, which meant one thing and one thing only, are now used in more plastic terms.

AVC: Having the language to describe things is essential to talk about them. But at the same time, it kind of fractures the conversation. Is that what you mean?

LB: It also enhances the conversation, because now when people say they’re a feminist, it’s truly a choice. Before it was either one or the other, and now they’re really choosing the word “feminist.” At these big women’s marches, you see younger women saying, “I have to be a feminist.” They’ve really thought it through. And they’re really bright. It’s not just an inherited word. We have to choose a battle, and we have to decide which issue we want to speak out against, because if we take on them all, we will stay embattled. [Laughs.]

AVC: I think that talking about labor like you do in Working Girls is important, looking at capitalism and how it takes advantage of women’s unpaid labor and devalues women’s labor.

LB: The thing is with sex work, sometimes people think it’s capitulating to the patriarchy because it’s dealing with men. And what I’ve always thought is that men think that because they have the money, they have the power. And my feeling is that women—and men, but I’m just talking about women because it’s an all-women brothel [in the movie]—that women have the resources. They have the resources of their body, which they’re willing to trade for a half an hour or an hour. Molly in particular prefers to have more “girlfriend experience” with her clients, her regulars, who are a little older.

Sex work does deal with men—it’s labor involving men. How does someone justify dealing with men? They can make fun of them, but Molly isn’t making fun of them in the room. Some of the scenes are comic—the ropes under the sink and the blind girl routine. The customers’ peccadilloes. But for some of the men, here’s a place where they can come in and show their vulnerabilities. And you think, “Wow, here are men who cannot express their sexual desire at home.” Sex work is underground, but it’s everywhere. It’s been going on since time immemorial, and will go on despite whatever [laws are put in place].

Another thing I just have to mention is that Working Girls comes from the ’80s. In downtown New York in the ’80s, there was a cross-fertilization of performance art. Annie Sprinkle did her famous piece where people looked into her vagina with a speculum. We had Ann Magnuson and Carolee Schneemann and Joan Jonas. There were theater groups like Wooster Group that used nudity in performance. And then there were strip clubs where people like Cookie Mueller worked. But it was such casual stripping! She never took her makeup off, because she had a kid and she wanted to be fully made up when she picked him up from school. She was always ready to hop on a stage. Everyone she knew would come to watch her, but it was more to hang out with her when she happened to be stripping.

So it was a milieu where artists and photographers and filmmakers could say, “Oh, you work at that place? Let me come and look at it when the madam isn’t there.” It was not an alien environment. It was mostly just people I knew. I knew about five or six people who worked at the place [Working Girls is based on]. I didn’t do a lot of research beforehand—I used to go in [to this brothel] when the madam wasn’t there and just tape everything, because my best friend worked there and I was fascinated by it. Nobody cared that I was recording, I just had to get out before [the madam] came back. It was only when I finished doing that that Sandra Kay, who I met who’d worked in a lot of other places, came on. She’s the one who has the other writing credit, because it was really about trying to make it as true as possible.

There’s a shot in Born In Flames of the real place, of somebody putting money on the bed. I wasn’t at that moment a huge fan of [Chantal Akerman’s film] Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai Du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles. Now it’s one of my favorite films. I actually stole a shot from Klute, of Bree looking at her watch during a session. But at that time, I hadn’t seen this kind of middle class prostitution [in a film], where it seems so ordinary, a stop on the way to Long Island for a half an hour.

But what I’ve seen over the years with the growth of social media, is a transformation of shame into pride. Now sex workers are really united and they’re very much about organizing to bring down SESTA-FOSTA. I’m doing an anthology of writings by strippers—not about them, but by them. Because of these anti-trafficking laws, they were hurt because they couldn’t advertise. A lot of them were forced out into the street, because the FBI was shutting down their websites. It’s been really destructive for them. Social media has allowed sex workers to organize globally. And it’s really about borders. It’s about immigration. It’s about protection. They can help with sex trafficking.

AVC: I feel privileged that now we’re able to hear about these things straight from the source.

LB: I used to think, back in the day, that there were two stories you could tell about sex workers: Getting out of the business, or you somehow fail or die. And now I understand, from my friend Jacq the Stripper–the third story is you sell merch. [Laughs.] These days there are T-shirts. Jacq, she retired [from stripping] and now she does cartooning and has a Patreon account. She’s a name! Now these women are more respected. They don’t have to necessarily continue in sex work, although some do. There’s a woman in Atlanta named Lux ATL who leads empowerment workshops for women and is very successful.

AVC: Pole dancing is a mainstream fitness class now.

LB: It’s true. The strippers and pole dancers have had arguments over the years, because a lot of pole dancers have said “I don’t strip.” Pole dancers tend to be snobby, they do more dance competitions. But yeah, Sheila [Kelly] started the first pole dancing classes in L.A. She was in the movie [Dancing At The] Blue Iguana. But where it really exploded was with Cardi B. I laugh, because one of my goddaughters, who was 18 at the time, was explaining to me how “WAP” was empowering! I need education from younger people. It’s always very helpful to have young people around to teach me tech and social media and about empowerment, because I have old-fashioned attitudes. [Laughs.]

But it’s interesting, because there’s also a renaissance in Andrea Dworkin, whose idea was that “all sex is rape.” There’s a film being made about her, and a biography. And I realize I have to revise my my thoughts about Andrea’s work, because at the time she and Catharine MacKinnon were against pornography and did not like films like Working Girls—although honestly, I don’t know if they even saw Working Girls. My feeling was I was a pro-pornography feminist because I felt we could just control the means of production. I didn’t like the [1978 Hustler cover] with the image of a woman through a meat grinder. I knew it was satire, but the image stays in your mind and I didn’t appreciate it. But at the same time there were women like Candida Royalle who were doing this very romantic pornography.

But I do see too many young girls who are taking their moves from the worst porn. The free stuff, it’s not helpful to women and young girls. And the fact that there is no sex education, that is devastating in this country in particular. I think that’s where we have to put our attention as a culture, is teaching. It’s still Our Bodies, Ourselves! It’s the most informative book ever!

AVC: It’s interesting that you say anti-pornography feminists weren’t necessarily directing ire at Working Girls in particular. I would have assumed that you would have gotten an earful after making that film.

LB: I did, from various places. Here and there. I don’t know if it came from Dworkin and MacKinnon directly. I think it came more generally from the culture. [Criticism] was brought up from two quarters, actually: One was from that [anti-pornography] quarter, about sex work and pandering to men and not seeing it as an individual film, but generically as one of those kinds of things. And the second one was from men who saw the film from the perspective of the johns and were offended by it.

And because it was a lower budget film—I shot it for $100,000, and then the total budget was $300,000—Miramax distributed it as a “come hither” movie. They did this weird thing when they were distributing it. I didn’t know anything about Harvey Weinstein and women at the time—he did throw desks against the wall, but that was seen as within the range of acceptable male behavior. But he advertised it for a raincoat crowd. I just figured they’d get in there and leave in 10 minutes.

AVC: I mean, yeah! There’s a deliberate lack of erotic quality to the sex scenes!

LB: Oh yes. I created it so that a man could not be turned on by it. It’s totally from the woman’s point of view. I really wanted every shot to be from an angle where Molly or the other women could potentially see themselves as they were being filmed, or could be nude in a scene by themselves. I worked very closely with our DP Judy Irola to make it as non-exploitative as possible. Everything was pre-rehearsed so it would not be pornographic. I completely ignored, except in one case, the idea that the sex was orgasmic at all.

It’s really about Molly’s experience. It’s a backstage look. I wanted [men in the audience] to identify with Molly, and not with the clients. Interestingly enough, over time, younger men have identified more with the women. But that took some time. At first, I think some men might have mistaken it for one thing, and then it was a bucket of cold water on that same thing! But it did okay, it did a couple million dollars in box office. So I think the right people found it.

But that moment is when I first met a lot of sex workers. I did panels with Margo St. James, who founded COYOTE, the group PONY, Prostitutes of New York, and with Carol Leigh, who coined the term “sex worker.” So it was very educational. Those women were so articulate, it was so helpful to me to hear them talk about it. That was the best for me, because to them [the film] was authentic, and that’s who I really wanted to like it most of all. What happened was the film disappeared because Miramax had lost all the prints. So it disappeared for a long time until this restoration. I think we were down to three DVDs.

AVC: Oh my god.

LB: I know. So I’m so grateful for this restoration. I did put the film on YouTube at the beginning of the pandemic specifically for sex workers, because it seemed really important. I love to do benefits for sex workers, and did a couple along the way whenever I was invited to, or when I was able to.

So yeah, at the beginning, there was some some pushback from the anti-pornography people. But the sex workers—they were formidable. Annie Sprinkle helped, and Candida Royalle helped. So many women from the sex industry helped, so it wasn’t just me. It was a whole battalion. The idea was that one could make the anti-pornography women seem very staid and academic. They seemed to be arguing from a viewpoint that wasn’t considering the experiences of women who maybe liked pornography, or secretly watched pornography. Who doesn’t look at pornography once in a while?

I was really afraid of approaching the subject in an academic way and really othering [the women]. Before I did Born In Flames, I had read a lot of Marxist texts, and that’s why I set the film after a social democratic cultural revolution. But when I was in the art world, I was reading too much art history, and it destroyed painting for me. So I didn’t want to read too much going in. But after I finished Working Girls, I met sex workers and I read everything. I needed to be able to be an ally, and when I’m questioned in Q&As, I don’t want to misrepresent anyone. That being said, I think one of the things that sex workers want is to be able to speak for themselves, which is why it’s important to have sex workers in the room—and also to pay sex workers.

I think it’s so amazing that the sex workers I know now are not only out, but are visibly out and reclaiming the word “whore.” Because in Working Girls, Molly is embarrassed when she’s called a “whore.” She hates it. Louise Smith worked with the actor in that scene, they were friends. They rehearsed it by themselves, and created the choreography. When he called her a “whore” in that scene, she started to cry, because it felt like an assault. The word had been so overloaded during the entire filming. Right. Now “prostitute” is not a good word, but “whore” has been reclaimed.

Everyone downtown who was kind of bohemian was actually pretty middle class. Everyone I knew who worked [at a brothel] could quit. And that was different from some of the other women who I met who couldn’t quit because of their life circumstances. They had to keep working. And so I really became aware of, “what do you do? What are your choices as women?” A couple of the women I knew also downtown did have 40-hour-week jobs, and it just felt like they weren’t getting as much work done. Because in working or writing or doing anything, you need some down time to think, you know?

It surprises me when people call Working Girls a documentary, because it’s so stylized. There’s downstairs, where clients come in, and then there’s upstairs. Upstairs it’s always incredibly stylized, with music and overhead shots just to make ellipses in time. And in the daytime, it’s lit one way, and at night it’s lit differently. Not quite like a horror movie, but darker and with an anxiety hanging over it.

AVC: The score sounds like a horror movie at times.

LB: That was intentional. I wanted you to have this prevalent overall feeling of anxiety, of something rumbling under the surface. It sounds like the clock, and time and money ticking under the surface, almost subconsciously. I spent a lot of time with that and with the mixer—which is my favorite thing, actually, working with the sound engineer toward the end. That was really great.

AVC: This might be a bit of a spoiler, but—I love how, at the very end of the movie, Molly is sleeping in bed and her eyes flip open again. It reminded me of the end of a horror movie where the villain pops back up, except the villain is that she has to go back to work.

LB: I wanted it to be an open question. Both films, Born In Flames and Working Girls, are about asking questions. At the end of Born In Flames, the question is, what happens after the last shot? Does violence work in a capitalist culture? And in Working Girls, it’s: You can quit your job, but then what do you do for money? Hopefully people will say, what could she do? What are her options? Some people don’t notice that shot when it pops up. That’s one thing I sort of regret, not having it sooner, because people don’t stay for it.

Le texte ci-dessus est une traduction automatique. Source: https://www.avclub.com/working-girls-director-lizzie-borden-on-standing-with-s-1847261667?rand=21407