Interview: Filmmaker Cary Fukunaga on Making ‘Beasts of No Nation’

by Alex Billington

October 15, 2015

«Sometimes the rules that you put on yourself till you’re figuring out how everything works don’t work in your favor.» Beasts of No Nation, starring Abraham Attah as Agu and Idris Elba, is a helluva film, and I couldn’t wait to talk to the director behind it. The Netflix Original Film premiered at the Telluride Film Festival (read my glowing review) but it wasn’t until just last week in New York City that I was able to catch up with writer/director Cary Fukunaga. Not only did he write and direct it, Fukunaga also shot the film as its cinematographer, and produced it. This is very much his film and he even spoke with me about how there were still sound tweaks he was making up to the last minute. This ended up being a fascinating, in-depth discussion about filmmaking with Cary Fukunaga and I wish I could’ve had more time with him.

Beasts of No Nation arrives in theaters and on Netflix starting October 16th. Cary Fukunaga’s full name is Cary Joji Fukunaga — he has directed the films Sin Nombre, Jane Eyre, and now Beasts of No Nation. He won an Emmy for his work directing «True Detective» (Season 1), and he has also made a few short films. In my strong review out of Telluride, I wrote that Fukunaga «has truly mastered the art of intimate, vibrant, powerful storytelling on the big screen. And to think that his career is still just starting, it’s remarkable.» He certainly agreed that his career is just starting, and also talked with me about the importance of sound, Hollywood tent-poles, the dynamics of a scene from Scorsese’s Goodfellas, shutter angle, and much more.

This interview was recorded on video, but the camera never saved the file at the end so instead I present the full transcription. Before the recording started, we were talking about the sound design and how important it is to see Beasts of No Nation in a movie theater because of the incredible sound design. He immediately started talking about working on the sound. Jumping right in from there…

Cary Fukunaga: Yeah, just trying in time to get the sounds right. We still had to drop our pencils before I thought we were really done. There’s a lot of sequences where we just hadn’t finished the sound in the way that I kind of had planned.

That’s interesting, in so much that I had figured you were done with it earlier in the year and they were just holding on to it.

Cary: No, no, no. We were posting up until… We had to deliver [the film] by the end of July, just to get everything ready with Netflix and getting the materials ready for spreading around the different territories. And I actually made them open up the sound again because I still just wasn’t happy with certain things.

Jumping ahead then — is sound one of the most important things to you?

Cary: Sound has always been really important to me. You would think that as a cinematographer and someone who just shot this film that the image would be the most important thing. But to me – not to, in any way, discount the work of any cinematographer – I feel like an audience can always forgive mediocre cinematography, but they’ll never forgive bad sound.

Think about it. That’s why you can shoot a movie on an iPhone and it’s okay as long as you’re not destroying everyone’s experience by really bad sound. That last step… it’s a funny process, post-production, because guys like Walter Murch, they are doing the sound design at the same time as the editing because sound is such a big communicator of – not only emotions from the music and everything else, but also the story being told. There’s narrative in the sound. There’s sequences in all my films that need sound design in order to finish the picture cut.

I can’t name names, but we had a different sound designer to begin with. It was a golden opportunity for him to do a bunch of different sequences where his sound design would dictate the flow or pacing of the edit. And he just never stepped up to do it. So we ended up parting ways. [Editor] Pete Beaudreau and I actually ended up doing the sound ourselves for that section.

I almost want to recommend you write a whole essay about this because the topic of forgiving cinematography over sound is really fascinating.

Cary: It’s interesting. I think sound people obviously know that. They’re like the quiet unsung heroes at the very end of the film process.

My first real question is: are you where you want to be right now in your career, in your life?

Cary: I think so. I saw an old friend recently and we were just sort of discussing how life has changed in the last 15 years. They told me that, «You seem to be exactly where you’d always hoped you’d be around this time in life.» So, professionally, career-wise, I have a lot of opportunity, I have a lot of projects I’m working on, but I still feel like I’m just starting. I think part of that is because it takes so long – like a movie, to get made. It takes so long to write something to feel like it’s right. I don’t think I’ve ever even gone into production where I’ve felt completely happy with the screenplay. So when you release the films, you don’t feel happy with what you’ve done completely, with what the entire package is, there’s things you would do differently and there’s things you kick yourself over.

But, to me it’s staring out because I’m also still experimenting with the genre, experimenting with craft and honing in on… I hate to use the word «signature», but honing in what is me.

Are you actively focusing on that or is it just kind of – you make a film and think about it in the long run?

Cary: It’s a bit of both. Some of it’s like, «Okay. What are the things I always fall back on in terms of problem solving in a certain narrative situation or even just a logistical situation? How do I handle covering this scene?» What were the scenes afterwards where, like, I look at the scene and I’m really happy with the coverage based on whatever time crunch we had. And I’m like, «Oh, actually that time crunch forced me to choose these angles, and just these two angles, and only having these two angles made the scene much more interesting than if I had more options.»

And part of the editing process, too, was actually pulling out… I hate when you’re constructing a scene and the logic of the camera is changing—sometimes close, sometimes wide, sometimes medium. It just seems arbitrary then. And you go back to films like Goodfellas, which I recently watched, and that famous scene with Joe Pesci and Ray Liotta where Pesci is threatening Liotta over, like, «What, do ya think I’m funny?»

And you watch that scene… First of all, what’s genius about that movie, too, is every scene by the end of the scene is seguing into some other unforeseen tension. That scene actually ends with the bill, where the guy asks for the bill. So one incredible moment actually is not over yet. By the end he’s breaking a glass with the guy’s head because he’s asking for the bill to be paid.

In that scene between Ray Liotta and Joe Pesci, it’s just two camera angles. There’s no close-up. It’s not necessarily a wide. It’s just two kinda mediums and you see a couple of guys around each of them. Even as Ray Liotta is studying Joe Pesci’s face, you never actually… the inclination would be punch in tighter, read him. Like, what’s going on in his eyes? Is he faking it? Is he real? Is he threatening him? They never do that. They keep it there. But in your mind, when you remember the scene you were close up in it, at least in my mind. Prior to me watching, I always thought, «Yeah, of course. He must have been up here on Joe and Ray.»

So what you are sort of getting at is – you’re trying to find out what your style is, in that Scorsese has these styles and you think, «Oh, I do this in my films»?

Cary: Well… I used to compete at sports. For me, the stuff I looked up to the most wasn’t always the most technically advanced tricks. It was the tricks pulled off the smoothest. So I thought a really well-executed backside 180 with a lot of style to me was more interesting than a 720 or a 900. Of course now the sport has progressed so far beyond where-ever it was when I was doing stuff. But there’s something about the simplicity of things. So I appreciate a scene like that because of the simplicity and not trying too hard to force an experience on the audience.

That’s not to say you can’t have style or so much memorable style in something. It’s just about also just simplicity.

You seem to challenge yourself with stories that are hard to tell or are not easy to pull off. Are you looking for these kind of stories, or do they find you?

Cary: Do you mean like Sin Nombre…

I’m impressed by your films that seem like such a hard story to tell, logistically challenging even, and yet when I watch it, it’s beautiful… what seems like it took a lot to put together, it comes out looking like it was easy to put together.

Cary: [To himself] What movie was it I saw recently where I was thinking about how…? Maybe it was reading about The Martian and just reading about… And Soderbergh says this, about, every 10 minutes starting a new film, keeping the audience leaning forward into the film. I don’t think… that’s a craft that I’m still working on. I don’t think I’ve got to the point yet where I can take any story and make it engaging all the way through. That’s masterful.

In terms of the hard stories, I don’t know about that part. I’m definitely trying not to… At least not too predictable kinds of stories where you think you know the ending 15 minutes, 20 minutes before it’s happening. You think you know what a character is going to say and do.

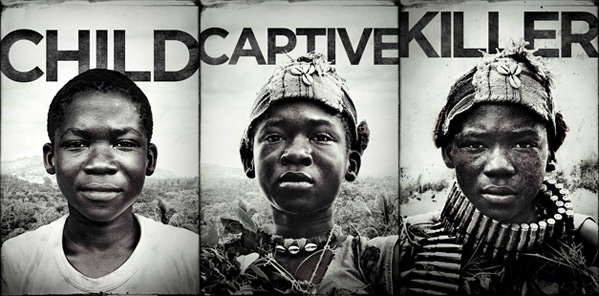

But I guess they’re not traditional. Even Beasts is challenging for an audience not only because of the violence and the subject matter of the child and what the child is – or, the children – is put through, but it’s also difficult because it shifts gears in places where you wouldn’t normally shift gears. You would usually be ramping up in the third act to some sort of climax; instead, I slow down in the third act. And to me it’s necessary to slow down. But it’s very difficult for the audience to… to many people it’s a turnoff. It feels boring. But to me it was a necessary change of gear to get back into the interior life of Agu Raza and just, constantly, through the sensational experience of the violence, numbing the audience.

You can portray as much as you want on screen, but the audience will make what they want to make of it. Do you find yourself struggling with the idea of, «I want to show this but the audience may not get it»? With Beasts you may not get people to stay all the way through, even though you’ve done everything as a filmmaker to present it in the best way.

Cary: There’s a couple things. You can have themes or concepts you’re trying to push through in a film. If it’s too intellectual, it’s usually not going to work. If it’s an intellectual concept and not an emotional concept, it’s going to go over most people’s heads. That’s never been anything that’s interested me. I like to put in subtext and things for people who are more familiar with the subject, things that they’ll be able to latch onto and recognize. But in terms of controlling whether someone sits through the movie or not, I’m well aware that even I don’t sit through every movie, even great movies. So, if someone, in this day and age with their phones or computers, are watching something and they get all the way through it that’s probably the highest compliment.

That’s interesting but also really sad. But at least you understand the current state of affairs.

Could you have only made this movie outside of Hollywood, in Africa, or would it have ever been possible through the Hollywood system?

Cary: Financing-wise or execution-wise?

Both.

Cary: Execution-wise, yeah. We didn’t break any rules, per se, in terms of safety. But content, would Hollywood have made a movie about this? Who knows? I certainly don’t think Hollywood would have made a movie like this without a sort of bankable, probably white actor sort of leading us through it. [Laughs]

Really? This story?

Cary: The action scenes were tough because we didn’t have any time. I had this amazing special effects artist out of the UK – Kevin Bitters and his crew, and they were like the A Team. In fact, they looked like the A Team. They all were so different, each and every one of them. They were each like identifiable cast members, in a way. They were like MacGyvers. They were able to make rain machines out of PVC pipes with lighters, packets to blow up bombs, things like that.

I think we finished shooting right on July 4th. So they even did an American fireworks show for us, even though it was South African. But these guys, we would do these scenes where I thought it was making it easier for us to put the battle far away, but it just meant we were seeing more at once. So when the commander and his inner circle are watching the battle take place further away, you’re seeing explosions and stuff go off. We have a limited number of explosions we can even use.

Why I’m asking is that all of this seems… this doesn’t seem so Hollywood. Even though you followed the rules and pulled it off, it almost seems like you were just shooting from the hip, like, «Let’s just make this.»

Cary: I talked to people I admire who do pretty crazy action sequences. Even Tarantino, they just go one step at a time and they do figure it out. And there are guys, obviously, like Ridley Scott who storyboards everything. If you look at Black Hawk Down, the action sequences in that are pretty detailed. I know they had a whole second unit going for months, because I want[ed] to use the crew. I recruited the crews that were doing the second unit for that movie in particular. And we didn’t have a second unit [on Beasts]. We were the second unit. So every little insert, everything we shot, we had to get. I had a lot of the same crew I had on «True Detective». So I knew that if we let insert shots go, we would never get them. On the end of «True Detective», we actually had to get another camera in that was just running insert shots nonstop. And I would go over and I would check it out, crime photographs or this and that. It was just constantly moving—inserts, inserts, inserts.

And so, it was important on this one that we picked up our inserts as we went, even at the detriment of our schedule. If I’m missing a detail that I need, this scene doesn’t work. And we weren’t ever going to catch it. Again, we couldn’t catch up at the end. In an action movie, typically you would have a lot more inserts—bullets hitting walls, things like that that we were never going to get. So I just planned without it.

I think it’s effective anyway. That’s what I like about it – it’s not conventional action, yet you still get such a visceral feeling, so much reality to it.

Cary: I allowed myself to break some rules that I normally made myself keep. On Sin Nombre, I wasn’t going to do any kind of bleach bypass or crazy treatment of the colors. We showed up shooting film then, so no cross-processing. I didn’t allow myself to do any slow motion, no shutter angle changes, you know the shutter angle effects the sharpness of the image, also how stuttery the fluid looks. The more stuttery it looks, the more like Saving Private Ryan, sometimes the more immediate and dangerous it feels. It’s a really easy trick to make a scene feel a little bit more, I guess, hyped up. In this movie I just was like, «I just gotta allow myself to do this.» I didn’t do it with «True Detective». There’s no action sequences in Jane Eyre, but I didn’t do it like that in Jane Eyre. I definitely didn’t do it in Sin Nombre. I’ve always felt like that shootout in Sin Nombre, it never quite worked because it felt too bright and safe and sort of too solid.

Sometimes the rules that you put on yourself till you’re figuring out how everything works don’t work in your favor.

What is the most important part of a production to get right? Is it the performances? Is it the story? Or is it truly the collaboration of everyone and everything?

Cary: I’m not really sure if there’s any step you can fuck up along the way. That’s what makes it hard. I always say even bad movies were hard to make. Because you can’t get it wrong. You can’t get the script wrong. Although you can make a pretty good film out of a mediocre script. But it doesn’t help. You have to get the casting right. You have to get the performances right. You have to get your material to edit with. You have to get the right score. You have to get the right cues of music, the right color correct, the right mix. Everything matters.

You’ve mentioned a couple of them, Goodfellas being one of them, what other kind of films or filmmakers have really inspired you?

Cary: I think the filmmakers who I watch their stuff and I really can’t see fault in it… there are other directors who I don’t like all their films… Let’s just say this. People who have films who I find faultless are people like: P.T. Anderson, [Alfonso] Cuarón, [Jacques] Audiard, [Martin] Scorsese, even bigger name directors like [Steven] Spielberg, who have been around longer. There are certain movies that are just completely without any… it doesn’t seem like anything was half-assed or a turd was polished; it was so purposeful all the way through. I’m sure I’m missing somebody [else to mention].

Where do you go from here and how do you maintain this levelheaded attitude and not let Hollywood ruin you?

Cary: I don’t know. I live in New York for one.

Good idea.

Cary: For me, like I said, I’m still starting off in my mind. I’m still working on things. I have genres I haven’t even experimented with and I want to play with. If I wasn’t writing a lot of my own things, I would probably be doing more commercials. And that’s a space I could be experimenting more. But I don’t even have time to do that now.

So I think I’m making more movies, making more shows… see what happens.

Are you going to fall down the «Hollywood rabbit hole», I guess I’ll ask?

Cary: What’s the «Hollywood rabbit hole»?

They suck up some great indie director making original films and put them on the next Star Wars or the next Spider-Man and then three movies and ten years later… Which is interesting because that’s a whole topic to discuss on its own.

Cary: I actually find that fascinating. Looking at a well-executed tent pole film, that’s really hard [to make]…

I agree. That’s what I’m wondering…

Cary: I like to look at those movies and see how they craft it…

But if they offered you Star Wars, would you take it?

Cary: I don’t know. I think it depends on the story. I wouldn’t do anything just because of a brand. I think I would have to feel like I see the movie in my head. As long as I see the movie in my head, then I think I could execute it. You know what I mean by that? But the idea of a tent pole film, it’s a different league. I wouldn’t say it’s a better or worse league. It’s just definitely more eyes on it, more pressure to deliver, to please, but not necessarily a challenge I’m afraid of. I wouldn’t consider it necessarily a sellout, because I see a challenge in it.

Thank you to Cary Fukunaga for talking with me + to Strategy PR for arranging the interview.

Cary Fukunaga’s Beasts of No Nation opens in select theaters nationwide + on Netflix starting October 16th. Highly recommend seeing this in theaters, it’s truly a big screen experience. For more — visit Netflix.

Find more posts: Feat, Interview

1

DAVIDPD on Oct 15, 2015

New comments are no longer allowed on this post.

Текст выше является машинным переводом. Источник: https://www.firstshowing.net/2015/interview-filmmaker-cary-fukunaga-on-making-beasts-of-no-nation/