Is there a responsible way to grow a franchise these days? Producer Basil Iwayk has some thoughts.

For most filmmakers working today, the challenges involved in building a successful franchise aren’t likely to come up. It’s hard enough to get one movie made, much less a whole fleet of them. By that same token, navigating today’s industry requires some understanding of the key market forces driving success, and IP is definitely one of them. Come up with an idea that can scale and you might have a shot at real sustainability.

However, this is not the most fertile time to embrace that concept. Warner Bros. Discovery’s “Shazam! Fury of the Gods” underperformed at the box office last weekend. Early tracking for “Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves” doesn’t look much better.

Meanwhile, Disney’s two biggest properties, Marvel and Star Wars, both seem to have hit an inflection point. Marvel fired longtime president of physical and postproduction Victoria Alonso this past week, a decision that seems to have stemmed at least in part from recent issues pertaining to the high volume of the MCU’s output and weakened quality as a result. Star Wars, meanwhile, continues to tumble with its Disney+ shows, as no amount of cute Baby Yoda closeups has succeeded at keeping “The Mandalorian” in the conversation the way it was when the show launched two years ago.

Related

Related

Franchises have become so cluttered and underwhelming that A.O. Scott, the stalwart film critic for The New York Times, gave up the gig to write about books this week and cited the preponderance of IP storytelling as one of his motivations.

On some level, this is an understandable frustration. Cinema thrives on originality and even world-building requires a certain level of creativity ingenuity. When everything looks like an extended variation on what came before, the whole concept of individual creation might feel like a lost cause. That’s why so many directors have wrestled with the question of whether or not to take a paycheck gig after their first feature. Why bother trying to do anything fresh?

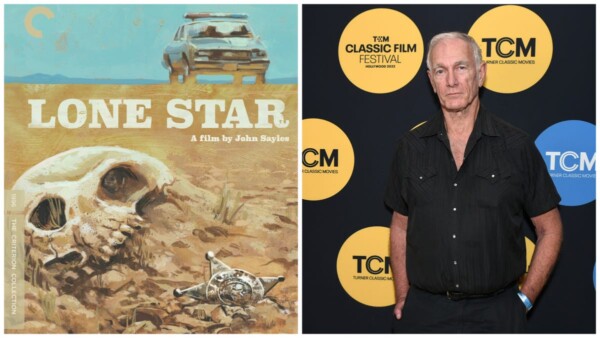

Lionsgate

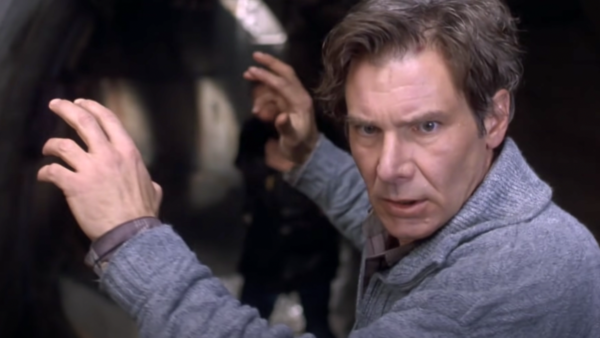

The highly-anticipated release of “John Wick: Chapter 4” provides a compelling answer to this question: It’s proof that franchises can be built, rather than replicated, from outside the system. And they can retain their appeal even as they grow.

Almost a decade ago, I attended a 10 a.m. press screening for the first “John Wick” at Fantastic Fest, Austin’s zany genre festival. I enjoyed watching Keanu Reeves kick ass and avenge his dead dog, but didn’t think much about the story’s long-term potential. After all, the appeal of “John Wick” has less to do with plot than pure experiential pastiche: It’s a deadpan martial arts comedy with bullet ballets to spare, its premise steeped in hyper-stylized action scenes, grim atmosphere and ostentatious mise-en-scene.

These movies offer a cinematic sugar rush, but they don’t try to overstate their appeal. They’re brainless, but that brainlessness is rooted in an actor and character who has genuine pathos. They’re like the fun parts of “Kill Bill” without the sarcasm and auteuristic indulgences. “Kill Bill” is a better movie, but “John Wick” is a more satisfying world, the kind of place that viewers want to revisit again and again.

That’s exactly why the movie ended up resonating as widely as it did. The idea of Reeves battling his way through endless foes in an invented universe was a better hook than any number of larger, more unwieldy cinematic universes that coincided with it (the underwhelming “Avengers: Age of Ultron” came out a few months later). The ensuing “John Wick” series hasn’t stumbled in part yet because each movie feels like a consistent extension of the mood piece preceding it. They never demand more from the audience than the audience wants of them, even as the aesthetic conceit remains intact.

All of this stands out because “John Wick” wasn’t made at the studio level. Thunder Road Films executive Basil Iwanyk set up the movie with independent investors and then sold it to Lionsgate. At Fantastic Fest, I remember speaking to multiple buyers who had passed on the project when it was presented it to them. Sources said that CAA was willing to sell the movie for around $6 million, a steep but not outrageous figure considering how profitable the series has been since then.

With “John Wick: Chapter 4” on track to continue the commercial success story for this series, I reached out to Iwanyk to discuss how he approached the challenge of growing a franchise from a producer standpoint. Iwanyk comes across as a a fast-talking, ultra-confident Hollywood pitchman for good reason: He worked his way through the ranks of Warner Bros. in the 1990s before starting his own production company, where he has built hits out of original ideas like “Sicario” and “Wind River,” both of which helped launch the career of “Yellowstone” superstar showrunner Taylor Sheridan. With “John Wick,” Iwayk has continued to prove that original IP has just as much a role to play in the current market as existing franchises.

Though this column usually deals with low-budget filmmaking challenges, Iwayk’s perspective has value here because he delves into the interdependence of independent and Hollywood productions. The “John Wick” saga could reach its own saturation point eventually, but for now, it’s the most valuable case study anyone invested in the IP game has to work with.

Here’s our conversation.

As usual, I invite readers to share their own reactions to the ideas expressed in this column by writing me: eric@indiewire.com

IndieWire: How hard was it to get the first “John Wick” released?

Basil Iwanyk: We financed the first film independently. So we finished the movie, we delivered the movie. We screened for every studio in town the same movie that everyone saw. We got passes from everybody except for Lionsgate. There were a couple of reasons for that. Some people genuinely loved the movie, but also, Lionsgate sold the foreign. In order to hold the foreign deals, there was a minimal screen commitment in the domestic distribution. A lot of the incentive for Lionsgate to release the movie was to keep the foreign deals. We actually thought we failed. It wasn’t the movie we thought it would be. The proof of concept was Keanu as a continuing action star, but the market spoke, and it said no.

When did you start to get an inkling that the movie could spawn a franchise?

We saw a trailer. Tim Palen, the head of marketing for Lionsgate at the time, put together a trailer. It tested really well. Remember, the first movie was really defined by the way it was such a ridiculous concept that these guys pulled off. It was clear that boy, Keanu still has it, and he’s really cool. People were just shocked. That first movie felt like we got away with something. It wasn’t as bad as we thought it would be. It only made like $44 million or something silly. We never went into it thinking there would be a sequel. But in the afterlife of the movie being discovered, in the enthusiasm about it, we noticed fan pages with questions about the world, who he was, his background. We saw a fan base that really wanted to know more. That’s when we thought to ourselves, “OK, maybe there’s a sequel here.”

But not multiple sequels.

We went into the first sequel thinking, “We already killed the dog and the wife died. What are you going to do to emotionally engage the audience?” When I was an executive at Warner Bros., I worked on “The Fugitive 2.” I thought to myself, “How the fuck do you do ‘Fugitive 2’?” Another innocent man accused of another murder? Or does it happen to the same guy again? We had a similar issue here, wondering if the audience would still care about going into the world. Frankly, when we screen the second movie and realized the audience was all in, we knew we had a franchise.

How did you assess the appropriate scale for the sequels? The cliché is that sequels are always bigger and costlier but not necessarily better. How did the initial movie establish expectations for what the sequels could cost?

The first movie cost net high twenties. Each movie got a little higher. The first movie was purely independent so nobody made money. Chad and David were scale; Keanu deferred most of his money because we had financial issues setting it up. I didn’t make a dime in the budget, only in profit participation. That was fine. It was like putting on a play at the local theater. The second movie was a little more normalized, but at the same time, the first movie didn’t make that much money theatrically. So there was still a little careful calibration of the budget. We couldn’t go too much higher. [“John Wick: Chapter 2” cost roughly $40 million.] We went to Rome, which expanded it. Of course you spend more money on the sequels, but where you spend the money is the trap most people fall into.

Explain that a bit more. Why do you have to spend more each time out?

Right off the bat, if you’re doing a sequel, everybody above the line gets paid more. Also, heads of the departments and crew know they’re in a franchise. They’re not cutting their salaries. You’re getting them at their market rate. I do think you’re going to spend more money because you want things to be better. It’s hard to articulate this. There’s a way to spend money for the sake of being bigger. We’ve all seen that before. It becomes mind-numbing. We spent more money to expand the world a bit. We wanted to expand to Rome in the second one, Morocco in the third one, and in the fourth one we went for it big time: New York, Paris, Germany. If you look at the car chase at the end of the first “John Wick,” it’s ridiculous: Three cars in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. That’s it. It had a charm to it. We knew we had to augment that more, but not just make them bigger.

Most sequels push harder and harder each time out until it gets ludicrous. When the “Fast and the Furious” guys went to space, I was almost embarrassed for them.

We’ve talked about this a million times. We’ll never be able to outspend the car chases in the “Fast and the Furious” franchise. So how do you do it differently? Not just in terms of how you stylize it, or how it’s choreographed, but in terms of the geography of it, the challenges of it, how it’s shot. Oftentimes, it’s not only how we make it bigger, but different from what we did before. What’s the next evolution of these things?

And how can you avoid redundancy.

We’re constantly trying to avoid falling into those traps. Chad and I saw where it worked and didn’t work. I don’t want to mention recent names, but sometimes you end up making “Moonraker,” and you’re like, “What just happened?” I think the audience wants some expansion, but not too much.

“John Wick: Chapter 4”

Murray Close/Lionsgate

The third movie had a reported budget of $75 million. What range would you place this one in?

I can’t say.

Was there a ceiling?

Listen, you try to be responsible. It’s not like we made “The Avengers.” The third movie didn’t make a billion dollars. It’s done well, it’s really well respected, and occupies a comfortable spot in the zeitgeist. But we don’t have the luxury that they do. It was never a question of the audience not wanting more. Each film has a signature action sequence or two. The question is always how to top that. It’s not like, “He fought 20 people in Times Square, so now he has to fight 100 people.” It’s about how to top the dog sequence in “John Wick 3.” After “John Wick 4,” it’s going to be about how to top the Arc de Triomphe sequence. It’s not only about size. Obviously, the Arc de Triomphe is bigger. It has to feel as cool if not cooler than the previous one. Sometimes that costs money and sometimes it doesn’t.

If you could be a bit of an armchair analyst for a second, consider the challenges facing the Marvel and Star Wars franchises. Disney is spending a lot of money on these movies and TV series with diminishing returns. The market seems to be oversaturated by them. Nobody benefits as a result. How do you withstand the pressure to go overboard with popular IP?

I don’t envy Marvel or DC where there’s constant demand for new and interesting stuff. You literally have to top some of the greatest, most commercial movies ever made. I always joke that I’ve made some awful, awful movies. People ask me, “What were you thinking?” We all thought we were making the right decisions. It’s not like I put my franchise hat on for the “John Wick” movies but take it off for “Gods of Egypt.” No, we don’t think that way. It’s the threading of a line to keep the franchises relevant as viewers evolve every year and a half while at the same time leave the audience wanting a little bit more. It’s a fine line. “Star Wars” is a perfect example. I love everything they put out, especially the Disney+ stuff. But you see the ratings on “The Mandalorian” and it’s frustrating. I grew up on “Star Wars.” Is there too much of it? I don’t think so. Is there too much Marvel stuff? Well, the bar is so high for these franchises.

You mean they’re set up to fail.

“Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania”

Courtesy of Marvel

I can’t imagine that pressure. We don’t have that. We’re kind of an underdog. We make up stuff as we go along. There isn’t some canon where people look back and go, “What about this?” I feel like we’re playing with a little bit of house money. To use a sports analogy: If you’re a Yankees fan, you’re expected to be in the World Series every year. If you’re not, that’s seen as a failure. That’s a lot of pressure. There’s a lot of money. I feel like “Star Wars,” Marvel, and DC are like the Yankees. And I think that’s bullshit.

You produced Taylor Sheridan’s “Wind River” and are a producer on “Wind River: The Next Chapter,” which he isn’t directing; you also produced “Sicario” and its sequel, both of which he wrote. In the years since the first one, Sheridan gave Paramount its biggest hit with “Yellowstone,” and now that show’s expanding universe is driving the studio’s overall strategy. What do you make of that particular IP play?

Listen, it’s unbelievable that this guy does it all himself. I knew he had an incredible work ethic and was as tough as they come. The thing he hit so successfully was that his Taylorverse is beloved not only by Middle America — which is the way people try to spin it — but my friends in New York and LA love it, too. They’re obsessed with it. I know people going back to watch “Wind River” and “Sicario” because of Taylor being a voice. If you had told me the guy who wrote “Hell or High Water” was going to be one of the great franchise creators in the modern history of television, I’d think there was no chance. But that’s why you have to focus on the core story and let the market tell you that you have a franchise.

At Sundance this year, you were a producer on “The Accidental Getaway Driver,” a movie that has yet to secure a U.S. distribution deal like a lot of films this year. What do you make of the challenges facing acquisition titles now?

“The Accidental Getaway Driver”

Ron Batzdorff/Courtesy of Sundance Institute

The funny thing about “Accidental Getaway Driver” is that it’s from the people who brought you “John Wick” and James Bond, since Barbara Broccoli is one of the producers. You know, we have 10 movies in post, from big movies to midsize movies to romantic comedies. For “Accidental Getaway Driver,” we believed in a film set in a kind of world and subculture with a cast that reflects that. By the way, the budget reflected that as well. It was one of the smallest movies we’ve ever been involved in. I think there’s a market for people to tell these niche stories. There’s no question that it’s harder than it’s ever been, but on a movie like that, you can’t try to make it commercial. You have to make sure it has street cred and artistic integrity that people will recognize. It’s not a big hook. You can’t hide the fact that it’s a relatively unknown cast of Vietnamese actors. You have to believe the audience will discover it over time despite the challenges.

So what is that audience since the film is still unsold?

It’s harder than it was. I’ve had films in festivals where you show it and it’s like Broadway back in the day: Wait for the reviews and then sell it. Now it’s much more measured and methodical. Only a few movies get the big festival announcements. Needless to say, we’re in discussions with a number of people. Who’s that audience? It’s the audience that’s going to want to see interesting filmmaking from a different point of view. This is the one thing I find pretty exciting in terms of the Netflix of it all. Audiences are a lot more open to foreign storytelling or storytelling that isn’t classic American storytelling. Granted, this is an American film, but the lens has opened up a lot more for audiences to see casts like this. There’s literally not one person in this cast who could be recognized by most viewers here. But it feels real and people will watch it because it feels like a part of the subculture they haven’t come into contact with. That’s appealing to people.

But is that appealing to buyers when they’re so worried about risk?

The market drives budgets of films. It just does. Yes, every once in a while, you have a filmmaker who says, “I need X,” and you’re like, “OK” even though it seems kind of silly. In my world, if the market tells me a movie costs $20 million, then it does. If I say that I need $30 million, I’m not getting that movie made. You do have to mold your film earlier in the process to know what the ultimate market will be. We mostly work with smart money. Silly money isn’t flying around Hollywood the way it used to. You need justification. Will the budgets go down? It depends on what you’re talking about. Did the budgets spike up during the streamer madness? Of course. But it’s finding its level. Is it nerve-racking that the streamer business seems to be ignoring the independent sector? A bit, but I think it’s finding an equilibrium between theatrical and the streamer world. It’s like trying to fix the plane while it’s in the air, but it’s getting to a healthier place.

This is certainly a more optimistic assessment than I’ve heard from a lot of people.

Eric, I’ve got to tell you something. Nothing drives me fucking crazier than people saying the sky is falling. Are you kidding me?

Mark Gill made that pronouncement 15 years ago.

I just read this new book, “Hollywood: The Oral History,” a whole history of Hollywood by Jeanine Basinger and Sam Wasson. It goes from the ‘20s to the ‘30s, the ‘40s to the ‘50s, and you see the same fucking argument, the same lament. People would say Thalberg listens to his preview audiences too much or whatever. There’s always been complaints like this. I think with theatrical coming back and the streamers still booming — they may be spending two instead of five gazillion dollars, but it’s still a lot of money — I just think it’s the most exciting time to be a content creator since I’ve been in the business. Everyone says, “They don’t make original movies now.” We do! We have 10 of them in post. If you look at it with the old rules, it’s frustrating, but you have to evolve. I’m incredibly optimistic about it.

You don’t think GenZ viewers are losing interest in movies and TV altogether?

No. Sometimes I look over my 12 or 15-year-old’s shoulder. They watch something for like 10 seconds and then swipe, swipe, swipe. It gives you a headache. But they love storytelling. They love being able to sit down and watch something. People love to mention the runtime on “John Wick 4,” and it drives me crazy. My 15-year-old binged every “Breaking Bad” episode over Christmas. My 21-year-old will wait on “Game of Thrones” and then watch like two years over the course of five snowy days. On the one hand, this generation keeps flipping through things; on the other hand, they don’t seem to have any problem with length. “Avengers” is directly appealing to the people you’re talking about. It made zillions of dollars and nobody gave a shit.

Still, you have to admit that attention spans have shifted.

I do think they reject things a little faster. Maybe the argument is that you have to catch them early on in the movie, but I have not seen evidence of that in the box office. I don’t see people saying movies need to be an hour and 20 minutes. There’s a difference between long and boring. No one wants boring.

”John Wick: Chapter 4” is now in theaters.

Check out earlier columns here.

Sign Up: Stay on top of the latest breaking film and TV news! Sign up for our Email Newsletters here.

Текст выше является машинным переводом. Источник: https://www.indiewire.com/2023/03/john-wick-producer-interview-basil-iwanyk-1234822813/