Wait ’til they get a load of her.

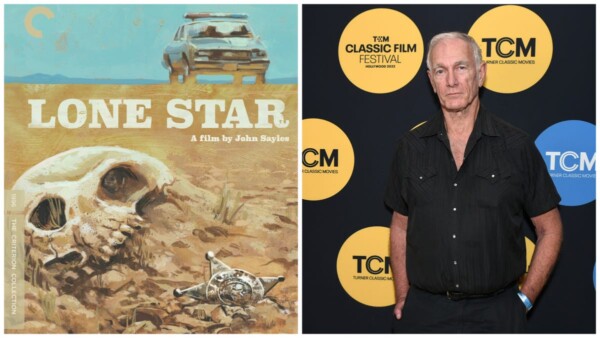

Vera Drew, the co-writer, director, and star of the Joker parody The People’s Joker, has ridden the Batwing to national prominence as only the creator of such an absurd work could. Produced on a dare, or, as she tells it, a $12 Venmo request to re-edit Todd Phillips’ Joker, Drew’s film spiraled from there, becoming, at one point, a re-edit of the entire Batman cinematic canon before settling into its final form: a crowdfunded, mixed-media transgender coming-of-age comedy parodying Joker, Batman, and the comedy world at large. However, on the eve of its 2022 premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, an unnamed media conglomerate sent an angry letter to Drew, “pressuring” her not to screen the film, fitting for a movie set in a world where comedy is illegal.

Following a months-long back-and-forth with her legal team, The People’s Joker is finally free. The film is exactly what it says it is and so much more. Though it contains the bones, structure, and iconography of Todd Phillips’ improbable billion-dollar grosser, People’s Joker is very much Drew’s story. She plays “Joker the Harlequin” in a Gotham City where Batman owns a streaming service, comedy is only available to those with the right training, and every aspiring comedian is a Joker—unless they’re a girl, then they’re a Harlequin. Having worked under luminaries from the alt- and mainstream comedy world, such as Tim Heidecker, Eric Andre, and Sacha Baron Cohen, Drew maps her professional journey onto Joker. It’s what makes People’s Joker so thematically winning: Her ultimate Jokerification comes from her desire to be a professional clown.

Vera Drew spoke with The A.V. Club about her relationship with comedy, Joel Schumacher, and, yes, the Caped Crusader, wondering, when it comes to the hostile response to her singular parody, why so serious?

The A.V. Club: Your resume is an embarrassment of riches of great comedy, especially On Cinema At The Cinema.

Vera Drew: My favorite soap opera.

AVC: Which season did you direct?

VD: Season 12. It was the season with all the “Heilots.” You know, Bill Maher ripped off my set.

AVC: For Club Random?

VD: [laughs] Yeah, it was that season.

AVC: The sets change with Tim’s hair on that show, especially now that they moved out of the movie theater. What reference points do you use?

VD: I can really only speak to that season because that was the only one I directed, but I think our main reference point was The Daily Wire. There were a lot of podcasts with men all sitting around talking and drinking scotch and smoking cigars in what looked like a sort of man cave. We definitely took that, and we wanted to make it a little bit more movie-centric. I was definitely the one that was like, “And there needs to be, like, bisexual lighting to it.” I thought that was going to be the thing that would make it a parody—making it look like a Virgin Megastore or like a Schumacher movie. But then Club Random came out, and it’s just exactly the same set. It’s the same lighting scheme.

There’s something about On Cinema. It’s like a giant chaos magic ritual. Every time they make something, it’s like ripping a hole open in the universe, and then reality shape-shifts into what we were parodying. It only happens with that show. I have worked on a lot of cool stuff, but there’s some sort of magic that On Cinema really taps into.

AVC: Regarding the film’s legality, there was almost a collective surprise that something like this could be made under parody laws. Robot Chicken has been on for 20 years, and it is just as offensive, if not more so, than anything in People’s Joker. Have we become too comfortable allowing corporations to parody themselves?

VD: I just think nobody’s ever done it the way I did it. There’s no precedent for what The People’s Joker is. There’s not one parody piece of media that people can point to and go, “Oh, it’s like that.” I think that’s really scary for people sometimes. But to me, that’s what’s exciting. Here’s a movie that you’ve never seen before. It’s playing with things you’ve seen a billion times, but it’s showing it to you in a way that you’ve never seen before.

Warner Bros. wouldn’t make a trans Joker parody. That’s maybe some of the apprehension. In general, I think people are comforted by corporations in America. We are all kind of in a space where we feel like orphans or something. So I understand why people would be in a position where they don’t get it, or they don’t particularly like what they’re seeing.

This was always going to be my first movie, and I’m so thankful that it is because I could never have imagined I would get to make something that would have this level of exposure at this point in my career and that would simultaneously get people so excited and then get a handful of other people, like, pretty up in arms and, and weird about it.

AVC: There are so many unsung heroes of the Batman mythos in your movie, like Bob The Goon and Mr. Myxlplyx. Was it satisfying to dig some of these characters up and write jokes about them?

VD: I just love Batman so much. I can’t stress that enough. I still see every single Batman movie that comes out and probably always will. But there are so many characters from that universe and aspects of that universe like “Super Sanity” or, you know, seeing the Red Hood mythos talked about in a way that’s more generalized and not just like, Joker used to be Red Hood.” Talking about it in a way that’s more mythic and stuff. It’s satisfying when I see people talk shit because I’m like, “Yeah, they haven’t seen it.” But if they’re Batman fans, I’m like, “This movie’s for you, dude! You should see it!” If you really actually love the comics, there are going to be things in this that you really like, latch on to, and are stoked that somebody else gives a shit about it enough to do a parody version of it.

Because I’m trans, my identity is immediately politicized, and it’s immediately politicized either in a neo-liberal, “Oh, they’re shoving the agenda down our throats way” or “Oh, she’s like one of those dirtbag leftist anarchist types.” I’m definitely not a moderate, but I don’t think the movie embodies either of those ideologies completely. Mr. J’s character is very heavily based on dirtbag left boys. He’s a gun-toting, leftist anarchist. I don’t want to say it’s critical of that, but it’s certainly not saying, “Hey, this is what everybody should be.”

The movie takes place in a universe where comedy is illegal, and that’s what I hear conservatives say all the time. So they should agree with the premise that I’m putting forward and see it from the perspective of “Yeah, comedy is heavily regulated and managed, and it’s not by people like me.” I’ve worked on every fucking cool alternative comedy television show for a decade. My first job was on season one of The Eric Andre Show, and it was hard for me to break out as a director and as a producer in that world after a decade of experience in it. I’m not saying it needs to be easier for girls or queer people to get into comedy, but I am trying to show the thing these edgelord, alt-right people are reacting to about woke culture and free speech, and I’m kind of with them. We live in a very reactionary time where people moralize everything. Media literacy is at an all-time low because we moralize every single thing that comes out. I also don’t think I am part of the elite just because I’m a transsexual. I think, if anything, I’m a villain. You know, I didn’t start an illegal comedy theater, but I really cut my teeth making my art, my personal art, at a public access station that I helped start a few years ago called Highland Park TV. That was my Red Hood theater, and I did that because comedy’s very inaccessible to, quote-unquote, marginalized identities.

AVC: There is an ominousness to the moment when Joker the Harlequin calls her boyfriend “Mr. J” for the first time. Obviously, Harley Quinn’s relationship with Joker is all kinds of fucked up. But what was it about the nicknames that you have such power? Why did you want to hit that?

VD: When you hear her call him that, you know exactly what their relationship is about to become. I fucking love that Birds Of Prey movie is a movie about moving on from that dynamic. And I really wanted to make something that was about that dynamic, but in a way that was honest.

The Mr. J character is based on a relationship that I had that was very traumatic, very intense, and abusive. But I wanted to make it a lot more nuanced because I really do think those kinds of codependent dynamics in queer relationships, they’re very identity-forming. I wanted to take that archetype of a toxic clown couple but talk about it in a way that was honest and hopeful and still real and grounded. I also didn’t want to make Mr. J an outright villain. He’s the only transmasculine character in the lead cast, I wanted him to have a softness while still really leaning into those archetypes.

AVC: In People’s Joker, Joker’s “Jokerfication” results from her struggle to become a comedian. She takes aim at comedy institutions that are integral to the entertainment pipeline, such as the UCB Theatre and Saturday Night Live. Did you or your cast have any concerns about that? Some of the cast, like Bob Odenkirk, came out of those places.

VD: I was concerned about involving people in it. I can’t stress enough: The views expressed about comedy in The People’s Joker are very much mine, and Bri LeRose’s to a certain extent, but I would even take more ownership of how angry it is at comedy. I grew up watching SNL. I wanted to be on SNL when I was a kid. If Lorne Michaels had come to any of my shitty improv shows when I was in my 20s and plucked me out of obscurity, I would have gladly taken his minimum-wage TV job. But at the same time, I wanted to tell an honest story about it.

UCB is like Scientology to some extent. I don’t know what it’s like now. I haven’t been there in years and please print that part of it because I know it’s rebranding now. I can’t speak to what it’s like now, but when I was there, it very much was gatekept. You had to pay thousands of dollars in classes to even get on a mainstage show, which is insane. When I got to UCB, I had already been doing comedy for years. I had been doing comedy since I was 13—just the most annoying 13-year-old on the planet, if you can imagine. I needed to make a big piece of art that not only criticized it but also talked about the good things about it.

In the movie, Lorne Michaels is played by Maria Bamford, who is probably my favorite comedian of all time, a national treasure. I love Maria, and I can’t believe she wanted to do the movie because she’s been around for a while. She cut her teeth in a lot of these scenes. She knows the shit that we face when we go into this world. Maria is one of the coolest, weirdest people making comedy. So, of course, she faced adversity.

She had one note. There’s a line in the movie where Lorne Michaels is convincing Joker the Harlequin to host the show that week. And Lorne starts spiraling, as I assume the real Lorne Michaels does, and starts rambling and saying, “Our writers on this show are so good, and I have no idea why the show is so bad.” It’s true too. I have friends who work on SNL. There are so many talented people who have come out of there and work there. But [Maria] saw the line, and she was like, “Listen, I don’t want to say the show is bad. Can I say that the show is uneven because that’s how I actually feel about it?” That’s a better version of the line, too, and it’s actually more true to how I feel about it.

I’m doing a lot of the stuff in this movie that SNL does every week. They always show characters who are intellectual properties that they don’t own in a parody context, so I’m clearly inspired by SNL despite thinking it’s part of our nuclear industrial complex.

AVC: How did Ra’s al Ghul become the improv guru at the comedy school, and why that character specifically?

VD: I love Ra’s al Ghul as a character in general. The idea that Batman studied not only martial arts but also mystical arts is one of the dumb, funny, fun, and cool things that I love about the Batman canon, so I wanted to do a parody version of that. Our version of Ra’s al Ghul did train Batman. Later in the movie, we find out that he was Batman’s comedy teacher, which might explain why Batman is upset about a few things in the movie. Also, I needed an Obi-Wan Kenobi-type figure in the film, and Ra’s al Ghul was the perfect archetype for that.

The perfect person to play that part was David Liebe Hart because this movie is talking about alternative comedy in a way that people have talked about David. It’s like, “Oh, is it okay to put this guy on TV? He’s so strange.”

I want to set the record straight: David Liebe Hart is the biggest Tim and Eric fan I’ve ever met and is obsessed with making comedy. He is a natural-born star. I worked with him on a show called I Love David that I wrote and directed with him. It’s about his life, and in the make the process of making that show, I had so many amazing conversations with him about art and spirituality and queer identity. He did become this Yoda-like figure in my life at various times.

But Ra’s al Ghul character was more based on my relationship with Tim Heidecker and when I worked with Sacha Baron Cohen. I worked with a lot of really cool, amazing comedy geniuses, and I’ve learned a lot from them. I wanted to talk about it in a way that was not only aggrandizing but also portraying them in an honest way. There’s a point in the movie where Joker the Harlequin has reached the end of her training, and—without spoiling it—Ra’s al Ghul is like, “I can’t encourage you to break the law, so I’m not encouraging you to do that. That is a decision you need to make for yourself.” There’s something about that that connects to my relationship with a lot of these comedy figures that I’ve gotten to work with. Tim’s the perfect example of this. He doesn’t always get what I’m doing but always hears it out. He’s always encouraging when it’s my own thing. With this movie, he’s he was like, “Look, I don’t know what the fuck you’re thinking making this, like, I don’t see it, but I’m proud of you and go for it.” That was something I really wanted to embody in this teacher character.

AVC: Ra’s al Ghul is not a perfect character. He works for the UCB and hangs out with Lorne Michaels. I imagine that is also true of your experience because, as we were talking about with regard to Maria Bamford, people you work with have connections to the wider comedy world.

VD: I think Sacha is in that character a lot too. He’d hate that. He’d probably hate that I said that. But Ra’s al Ghul in the movie is processing the experience of working on Who Is America with Sacha. Sacha’s a genius. I loved working with him. I looked up to him my entire life as a comedic performer, just one of the greats. And he also has a lot of rules about how you make stuff. One of his biggest rules was you can’t have two jokes happening at once. You can only do one joke at a time because that’s all that people can take in. And it would drive me nuts because that’s very much not my thing, as you can tell from my movie. I wanted to go out of my way in this film to break that rule but also talk about that idea in an honest way because I was the lead editor on Who Is America? They hired me to make Sacha Baron Cohen’s vision, so his notes, his concerns, and his rules about comedy and storytelling are coming from his experience of being a millionaire comedian who’s making his comeback as these Borat-type characters. My concerns as a stinky artist, little pop punk, trans girl are very different from that of an established comedic icon, who, yeah, still maybe embodies punk aesthetics but has a few more people they need to answer to now.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Текст выше является машинным переводом. Источник: https://www.avclub.com/the-peoples-joker-interview-vera-drew-1851364943